Journal of Geo-information Science >

Analysis of Life Expectancy and the Spatial Differences of Its Influencing Factors of Chinese Residents

Received date: 2020-10-15

Online published: 2021-11-25

Supported by

National Natural Science Foundation of China(41571082)

Copyright

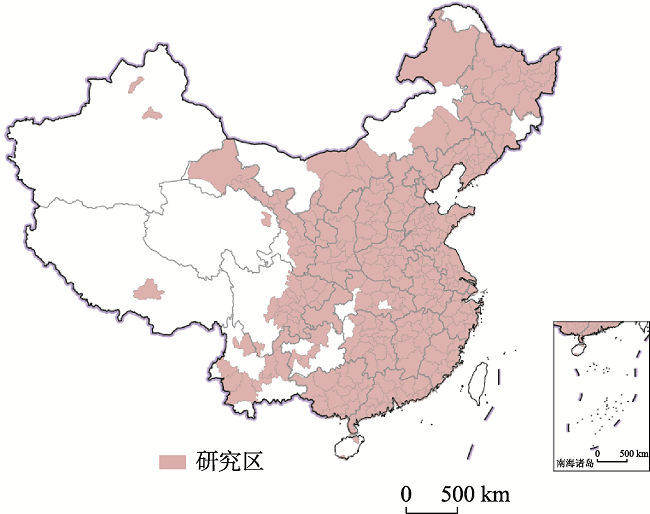

Good Health and Human Well-being is one of The Sustainable Development Goals proposed by the United Nations, and increasing the life expectancy is a significant step towards this goal. Due to differences in the natural environment and social development of Chinese cities, understanding the factors that affect life expectancy in different regions is the key to formulate urban public health policy. Based on the data of 286 cities in China in 2015, this paper used exploratory regression, ordinary least squares, and geographically weighted regression to screen out the most relevant influencing factors to life expectancy and explore their spatial differences. Then, the two-step cluster analysis was used to make targeted policy recommendations for each type of cities. The results show that: (1) Economic development, educational conditions, and medical facilities had a significant positive impact on life expectancy, while average altitude and environmental pollution had a negative impact; (2) Compared with other regions, economic development in the southeast region had a greater impact on local life expectancy; medical facilities in the northeast and southwest regions had a higher degree of promotion of life expectancy for its residents; education conditions in the northern region had a higher impact on the life expectancy of local residents; average altitude had the greatest impact on the life expectancy of residents in the West region; The life expectancy of residents in the northwest region was more susceptible to the negative impact of environmental pollution than in other regions; (3) Cities were divided into three categories based on spatial differences, and the key factors affecting the life expectancy are economic development and environmental pollution, educational conditions, and medical facilities in order. City managers in each category of cities should pay attention to different factors to increase their life expectancy.

ZHANG Ziwei , HUANG Qiuhao , LU Yu , LI Manchun , CHEN Zhenjie , LI Feixue . Analysis of Life Expectancy and the Spatial Differences of Its Influencing Factors of Chinese Residents[J]. Journal of Geo-information Science, 2021 , 23(9) : 1575 -1585 . DOI: 10.12082/dqxxkx.2021.200607

表1 预期寿命影响因素的选取依据Tab. 1 Selection basis of factors affecting life expectancy |

| 维度 | 影响因素(简称) | 选取依据 |

|---|---|---|

| 经济因素 | 人均GDP(PCGDP) | 文献[7]、[36]、[37] |

| 人均储蓄存款余额(PCSDB) | 文献[38]、[39] | |

| 医疗设施 | 千人床位数(HB) | 文献[11]、[40] |

| 千人医生数(DP) | 文献[10]、[41] | |

| 环境污染 | 人均SO2排放量(PCSO2) | 文献[29]、[40] |

| PM2.5 | 文献[42]、[43] | |

| PM10 | 文献[29]、[44] | |

| 自然条件 | 平均海拔(AE) | 文献[17]、[19] |

| 年平均温度(AT) | 文献[18]、[19] | |

| 年均降水量(AP) | 文献[17]、[18] | |

| 教育条件 | 教育从业人员占人口比例(POE) | 文献[45] |

| 千人学校数(PCSCH) |

表2 十二项预期寿命影响因素的探索性回归分析结果Tab. 2 Exploratory regression analysis results of twelve factors affecting life expectancy |

| 校正R2 | AIC | VIF | 影响因素组合 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.48 | 1122.13 | 2.52 | +PCGDP***, | -AE***, | +POE***, | +HB**, | -PCSO2*, | ||

| 0.48 | 1123.73 | 2.52 | +PCGDP***, | -AE***, | +POE***, | +HB**, | -PM2.5**, | +PCSCH | |

| 0.48 | 1123.82 | 3.26 | +PCGDP***, | -AE***, | +POE***, | +HB**, | -PM2.5**, | +DP | |

| 0.47 | 1124.21 | 2.87 | +PCGDP***, | -AE***, | +HB**, | +AT*, | -PCSO2*, | -PM10* | |

| 0.47 | 1125.43 | 3.26 | -AE***, | +PCGDP***, | +POE***, | +HB**, | -PCSO2*, | +DP*, | -PM10 |

| 0.47 | 1125.84 | 2.87 | -AE***, | +PCGDP***, | +POE***, | +HB**, | +DP*, | -PM2.5, | -PCSO2 |

| 0.47 | 1125.93 | 3.31 | +PCGDP***, | -AE***, | +POE**, | +DP**, | +HB*, | -PCSO2, | +PCSDB |

| 0.47 | 1126.48 | 2.61 | +PCGDP***, | -AE***, | +POE***, | -PCSO2*, | +DP* | ||

| 0.47 | 1126.84 | 3.24 | +PCGDP***, | -AE***, | +POE***, | +HB**, | +DP | ||

注: 加减号代表系数的正负;***, **和 *分别代表显著性水平为1%、 5%和10%。 |

表3 筛选后预期寿命影响因素的描述性统计Tab. 3 Descriptive statistics of factors affecting life expectancy after screening |

| 影响因素 | 最小值 | 最大值 | 平均值 | 标准差 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 千人床位数/张 | 1.71 | 13.58 | 4.65 | 1.63 |

| 人均GDP/万元 | 1.02 | 20.02 | 4.96 | 2.93 |

| 人均SO2排放量/kg | 0.03 | 224.89 | 17.85 | 26.28 |

| 平均海拔/m | 1.32 | 4814.85 | 533.78 | 648.10 |

| 教育从业人员占比/% | 0.65 | 3.44 | 1.25 | 0.41 |

表4 预期寿命影响因素的OLS回归分析结果Tab. 4 OLS regression analysis results of factors affecting life expectancy |

| 影响因素 | 系数 | 标准误差 | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| 截距 | 76.67*** | 0.10 | |

| 千人床位数 | 0.40** | 0.16 | 1.96 |

| 人均GDP | 0.59*** | 0.19 | 2.52 |

| 人均SO2排放量 | -0.27* | 0.15 | 1.51 |

| 平均海拔 | -0.25*** | 0.15 | 1.44 |

| 教育从业人员占比 | 0.48*** | 0.14 | 2.24 |

注: ***,**, * 分别代表显著性水平为1%,5%和10%。 |

图6 GWR模型回归系数的二阶聚类分析结果Fig. 6 Two-step cluster analysis results of the regression coefficients of the GWR model |

| [1] |

郭文杰, 秦昆, 毛宗福, 等. “一带一路”成员国居民健康状况的时空统计分析[J]. 地球信息科学学报, 2020, 22(5):1133-1141.

[

|

| [2] |

李畅, 王安丽, 龚胜生, 等. 中国中部六省预期寿命时序加密估算研究[J]. 地理学报, 2020, 75(10):2269-2280.

[

|

| [3] |

郭玉玲. 中国人均预期寿命时空变化及影响因素分析[J]. 中国卫生政策研究, 2018, 11(8):44-49.

[

|

| [4] |

中共中央国务院印发《“健康中国2030”规划纲要》[J]. 中华人民共和国国务院公报, 2016(32):5-20.

[ The outline of Healthy China 2030 Plan[J]. Gazette of the State Council of the People's Republic of China, 2016(32):5-20. ]

|

| [5] |

中华人民共和国外交部. 变革我们的世界: 2030年可持续发展议程2016[EB/OL]. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/ziliao_674904/zt_674979/dnzt_674981/qtzt/2030kcxfzyc_686343/t1331382.shtml

[ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable[EB/OL]. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/ziliao_674904/zt_674979/dnzt_674981/qtzt/2030kcxfzyc_686343/t1331382.shtml

|

| [6] |

|

| [7] |

齐亚强, 李琳. 中国预期寿命变动的地区差异及其社会经济影响因素: 1981—2010[J]. 中国卫生政策研究, 2018, 11(8):29-35.

[

|

| [8] |

明艳, 董志勇. 我国人口预期寿命的影响因素分析[J]. 学理论, 2010(4):47-50.

[

|

| [9] |

|

| [10] |

|

| [11] |

董惠玲, 任桂芳, 宁佩, 等. 基于地理加权回归的老年人口健康预期寿命影响因素分析[J]. 中国卫生政策研究, 2020, 13(2):73-80.

[

|

| [12] |

|

| [13] |

|

| [14] |

|

| [15] |

|

| [16] |

|

| [17] |

|

| [18] |

|

| [19] |

|

| [20] |

|

| [21] |

|

| [22] |

|

| [23] |

|

| [24] |

|

| [25] |

王五一, 李永华, 李海蓉, 等. 中国区域长寿的环境机制[J]. 科学决策, 2015(1):1-12.

[

|

| [26] |

|

| [27] |

|

| [28] |

|

| [29] |

|

| [30] |

|

| [31] |

中国科学院资源环境数据云平台. 中国海拔高度空间分布数据[DB/OL]. http://www.resdc.cn

[ Resource and Environment Data Cloud Platform. China's altitude spatial distribution data[DB/OL]. http://www.resdc.cn

|

| [32] |

中国科学院资源环境数据云平台. 年平均降水量空间分布数据[DB/OL]. http://www.resdc.cn

[ Resource and Environment Data Cloud Platform. Spatial distribution data of annual average precipitation[DB/OL]. http://www.resdc.cn

|

| [33] |

中国科学院资源环境数据云平台. 年平均气温空间分布数据[DB/OL]. http://www.resdc.cn

[ Resource and Environment Data Cloud Platform. Spatial distribution data of annual average temperature[DB/OL]. http://www.resdc.cn

|

| [34] |

EU Science Hub. Gridmaps of PM2.5 and PM10[DB/OL]. http://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu

|

| [35] |

国家统计局城市社会经济调查司. 中国城市统计年鉴(2016)[M]. 北京: 中国统计出版社,2016.

[ Department of Urban Social and Economic Investigation, National Bureau of Statistics. China City Statistical Yearbook (2016)[M]. Beijing: China Statistics Press, 2016. ]

|

| [36] |

|

| [37] |

|

| [38] |

杨芊芊. 长寿风险、主观预期寿命与家庭资产配置[D]. 杭州:浙江大学, 2019.

[

|

| [39] |

Population aging, fertility and social security[M]. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

|

| [40] |

|

| [41] |

|

| [42] |

|

| [43] |

|

| [44] |

|

| [45] |

刘建立. 我国人口受教育程度的省际差异及其影响因素研究[D]. 上海:华东师范大学, 2013.

[

|

| [46] |

|

| [47] |

|

| [48] |

|

| [49] |

|

| [50] |

|

| [51] |

|

| [52] |

|

| [53] |

汪存友, 余嘉元. SPSS两阶聚类法如何自动确定聚类数[J]. 中国卫生统计, 2010, 27(2):202-203.

[

|

| [54] |

|

| [55] |

|

| [56] |

|

| [57] |

|

| [58] |

|

| [59] |

|

| [60] |

杨明旭, 鲁蓓. 中国2010年分省死亡率与预期寿命—基于各省第六次人口普查资料[J]. 人口研究, 2019, 43(1):18-35.

[

|

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |